The Naoshima Chronicle: Pollution, Regeneration, and the Art of Coexistence—How Industry and Ecology Meet on Japan’s Inland Sea

In the tranquil waters of Japan’s Seto Inland Sea lies a small island called Naoshima, part of Kagawa Prefecture.

At first glance, Naoshima appears modest—a hilly island of only about 8 square kilometers, dotted with small fishing villages and surrounded by a calm, silver-blue sea. Yet over the past half century, this unassuming place has undergone one of the most extraordinary transformations in modern Japan: from an industrial site of copper smelting and pollution into a world-renowned symbol of environmental regeneration, contemporary art, and architectural beauty.

Today, Naoshima is celebrated globally as the Island of Art, where modern architecture by Tadao Ando harmonizes with nature and art installations by some of the world’s leading artists breathe life into the island’s landscape. But this rebirth was neither simple nor immediate. It is the story of how an island of industry and hardship gradually became a living canvas of art, ecology, and human connection.

I. The Industrial Beginning: Copper and Modernization

Naoshima’s modern history began in 1917, when the Mitsubishi Group—then expanding its industrial empire—chose the island as the site for a copper smelting plant. At that time, Japan was industrializing rapidly, and the Seto Inland Sea, located between Honshu and Shikoku, provided excellent maritime routes for shipping ores and products.

Naoshima’s selection was primarily practical. The island offered:

- A strategic coastal location near major shipping lines;

- Natural isolation, ideal for heavy industry;

- And, crucially, the possibility to disperse pollutants away from urban populations.

Thus began the era of Naoshima Smelter, operated by what would later become Mitsubishi Materials Corporation. The plant produced refined copper by processing imported ore, and for decades it formed the backbone of the island’s economy. Generations of local residents worked at the plant or in related industries.

However, prosperity came at a cost.

II. The Dark Years: Pollution and Environmental Damage

The smelting process released sulfur dioxide gas and other byproducts that devastated the local environment.

By the mid-20th century, much of Naoshima’s vegetation had withered.

Trees on nearby hills turned bare and gray; crops failed; fish populations declined due to acidified runoff.

This was not unique to Naoshima—many industrial sites in Japan suffered similar fates during the nation’s postwar economic boom—but for a small island, the impact was particularly severe.

Residents who relied on fishing and agriculture struggled, and the island gained a reputation as a “polluted industrial site.”

For many, Naoshima symbolized the price of modernization: economic success achieved at the expense of nature and community well-being.

III. Turning Point: Environmental Recovery and Reflection

In the 1970s, Japan entered a new era of environmental awareness.Nationwide movements against pollution had led to stricter regulations, and companies were increasingly pressured to reduce emissions.

Mitsubishi responded by launching a massive reforestation and environmental restoration program on Naoshima. The company planted tens of thousands of trees, rebuilt soil, and introduced systems to clean industrial exhaust. Over the following decades, the island’s hills gradually regained their green color.

This process was more than ecological repair—it was a symbolic act of atonement and renewal.

Naoshima, once defined by its industrial smoke, began to reinvent itself as a site of coexistence between human activity and nature.

Still, few could have predicted that art would soon become the next catalyst for change.

IV. The Arrival of Art: Soichiro Fukutake and Benesse’s Vision

In the late 1980s, Soichiro Fukutake, then president of the education and publishing company Benesse Corporation(formerly Fukutake Publishing), visited the island.

Fukutake, whose family hailed from nearby Okayama, envisioned a new kind of cultural project—one that would combine nature, art, architecture, and community.

He believed that Japan’s rural regions, often declining in population, could be revitalized not through large-scale development but through spiritual and cultural enrichment. Naoshima, with its quiet landscape and history of environmental struggle, seemed the perfect canvas for this experiment.

“Art should not be confined within museums,” Fukutake would later say.

“It should exist in harmony with nature and with people’s daily lives.”

In 1989, Benesse began collaborating with architect Tadao Ando, renowned for his minimalist designs using raw concrete and natural light. Their shared philosophy—harmony between architecture and landscape—became the foundation of Naoshima’s rebirth.

V. The Birth of Benesse House (1992): Art You Can Live In

The first major project was the Benesse House Museum, completed in 1992.

Designed by Tadao Ando, it was a radical concept: a museum and hotel in one. Visitors could stay overnight within the museum, surrounded by works of contemporary art, and experience them in the changing light of day and night.

The architecture was not meant to dominate the scenery but to blend into it.

Concrete walls framed views of the Seto Inland Sea; open courtyards invited wind and sound; sunlight moved through geometric spaces like a living artwork.

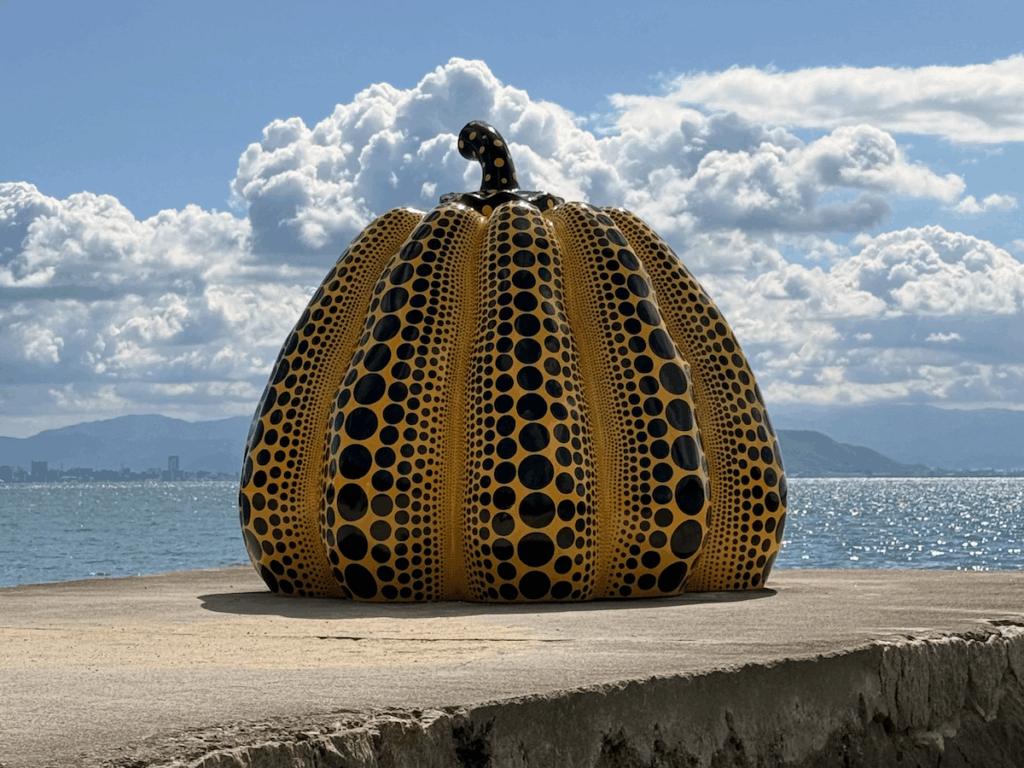

Artists such as Yayoi Kusama, Richard Long, David Hockney, and Bruce Nauman contributed works that interacted with the natural surroundings. Kusama’s “Pumpkin”, a bright yellow sculpture sitting quietly on a pier, would later become the island’s most iconic image.

Still, the introduction of art tourism to a small industrial island was not without friction.

VI. Initial Reactions: Confusion and Skepticism

When Benesse’s project began, many of the island’s roughly 3,000 residents were puzzled.

“Why bring art here?”

“How will a museum help our livelihoods?”

For decades, Naoshima’s identity had been defined by industry and labor. The idea that “art” could offer economic or cultural benefit seemed abstract, even elitist.

Benesse and the town government therefore worked carefully to build trust:

- Local workers were employed in construction and maintenance;

- Residents were invited to openings and community events;

- Profits were reinvested in public facilities and environmental programs.

Through these small gestures, art slowly began to be seen not as an invasion, but as a collaboration.

VII. The “Art House Project” (1998): Art within Daily Life

A true shift in local perception came with the launch of the “Art House Project” in 1998.

Instead of building new museums, Benesse and Ando turned their attention to the village of Honmura, a residential area of old wooden houses and narrow lanes.

Vacant houses were restored and transformed into art installations by leading artists such as:

- Tatsuo Miyajima, whose digital counters symbolized the flow of time;

- Hiroshi Sugimoto, who created a meditative glass structure inspired by Shinto shrines;

- James Turrell, whose works explored light and perception.

Unlike traditional galleries, these works were woven into the fabric of the community.

Visitors would wander through Honmura’s alleys, encountering artworks between ordinary homes where locals still lived. Children played near art installations; shopkeepers chatted with tourists.

In this way, art became not an isolated attraction but part of daily island life.

The residents themselves became informal guides and storytellers, bridging the gap between visitors and their town.

VIII. The Residents’ Transformation: From Skepticism to Pride

As tourism increased, some residents began running guesthouses, cafés, and small shops catering to visitors.

Economic benefits were tangible, but something deeper also changed: the way people saw their own island.

“We used to think Naoshima was just an industrial place,”

said one elderly resident in an NHK interview.

“Now people come from all over the world to see it.

I feel proud when I guide them around.”

For younger generations, the island’s identity was being rewritten.

Children took part in art education programs, created in collaboration with Benesse and local schools. They learned not only about art but also about the importance of nature, community, and history.

Some later returned as guides, curators, or artists themselves—helping sustain Naoshima’s new life.

IX. The Chichu Art Museum (2004): Art Beneath the Earth

In 2004, a new landmark opened: the Chichu Art Museum, meaning “art beneath the earth.”

Once again designed by Tadao Ando, this museum was built almost entirely underground to minimize its impact on the surrounding landscape.

Natural light, carefully calibrated through skylights and apertures, illuminates the artworks—creating a constantly shifting experience depending on the time of day and season.

The museum houses only three artists:

- Claude Monet, whose Water Lilies are displayed in a room designed to evoke the serenity of his garden at Giverny;

- James Turrell, whose light installations immerse viewers in pure perception;

- Walter De Maria, whose monumental sculpture unites geometry, gravity, and light.

Chichu Art Museum epitomizes Naoshima’s philosophy:

art, architecture, and nature existing in perfect balance.

It also embodies a deep Japanese aesthetic value—ma, the beauty of space and silence.

X. The Present-Day Smelter: From Industry to Recycling

While art was transforming the island’s cultural identity, the Mitsubishi smelter was quietly transforming as well.

Today, the Naoshima Smelter & Refinery remains active, but its mission has evolved from producing copper from ore to recycling precious metals from urban waste—so-called “urban mining.”

Discarded electronics, circuit boards, and metal scraps from around the world are refined on Naoshima, yielding pure copper, gold, silver, and palladium.

The plant has also introduced state-of-the-art environmental controls:

- Sulfur dioxide is captured and converted into industrial-grade sulfuric acid.

- Wastewater is purified.

- Emissions are strictly monitored.

Thus, the very industry that once polluted the island has become a symbol of circular economy and environmental technology.The narrative of destruction has been transformed into one of regeneration—a parallel to the island’s artistic rebirth.

XI. Harmony of Opposites: Industry and Art, Past and Future

Naoshima’s uniqueness lies in its duality.t is simultaneously a site of heavy industry and avant-garde art;a space of human labor and spiritual contemplation.

Visitors standing on the beach can see, in one direction, the smokestacks of the smelter; in the other, the concrete minimalism of Ando’s museums. Far from clashing, these two presences tell a continuous story: of Japan’s industrial modernity evolving into ecological and cultural maturity.

In this coexistence, Naoshima demonstrates that art and industry need not be opposites. Both can contribute to human creativity and sustainability when guided by reflection and care.

XII. The Human Dimension: Art as Dialogue

What truly makes Naoshima extraordinary is not just its architecture or artworks but its people.

The residents’ willingness to engage with unfamiliar ideas—to open their homes, to guide visitors, to participate in cultural exchange—made the project possible.

Art on Naoshima does not impose; it converses.

It asks both locals and visitors to reconsider the meaning of “beauty,” “community,” and “nature.”

The island’s success also inspired neighboring islands, such as Teshima and Inujima, to join the Benesse Art Site Naoshima network. Together, they form a constellation of art and sustainability projects across the Seto Inland Sea, transforming a once-forgotten region into a cultural archipelago known worldwide.

XIII. Global Recognition and the Setouchi Triennale

In 2010, the Setouchi Triennale—an international art festival—was launched, featuring dozens of islands and artists.

Naoshima served as its heart. The festival’s aim was not only to attract tourists but to revitalize rural communities and share the spirit of coexistence between people and nature.

Each Triennale brings new installations, performances, and collaborations, ensuring that the art on the islands continues to evolve.

Through these ongoing efforts, the Seto Inland Sea has regained cultural and ecological vitality, and Naoshima has become a global model for regional regeneration through art.

XIV. Legacy and Meaning: The Island as a Mirror of Japan

Naoshima’s transformation mirrors Japan’s own modern journey:

| Era | Theme | Naoshima’s Role |

| Meiji to early Showa | Industrialization | Birth of the copper smelter |

| High Growth (1950–70s) | Pollution and progress | Environmental damage |

| Late 20th century | Reflection and restoration | Reforestation, recovery |

| 1990s onward | Cultural and ecological rebirth | Art and sustainability |

This continuity gives Naoshima profound symbolic power.

It tells a story of repentance, renewal, and hope—a story that Japan, and indeed the world, can learn from as we face the challenges of climate change and cultural homogenization.

Conclusion: The Island of the Future

Today, Naoshima is no longer merely an island of copper or concrete.

It is an island of ideas—a living laboratory where art, ecology, and community coexist.

Visitors who step onto its shores sense a quiet harmony between the human and the natural, the past and the future. The sea breeze carries not the smoke of industry but the echoes of creativity.

As the sun sets behind Ando’s austere forms and the gentle waves lap against Kusama’s yellow pumpkin, one feels the essence of Naoshima’s message:

That even the most wounded landscape can heal;

that art can emerge from the ashes of industry;

and that the small, when filled with meaning, can touch the vast.

Naoshima’s journey from smelter island to the Island of Art stands as a testament to human imagination—

to the power of vision, humility, and collaboration to turn a scarred place into a beacon of beauty.